The piano is certainly the most versatile of musical instruments invented by man. I know that it can’t produce the delicate quarter tones that the violin or the flute can do. It isn’t either well-adapted to the Indian raga or Japanese gagaku. West African percussions, maybe, could be produced by banging on a Steinway, but that’s not the intention of the instrument. But I maintain: it is the most versatile instrument invented by man. As evidence, I suggest my experiences from a small number of performances held in New York City in the past couple of months that I was able to attend.

Ayako Shirasaki @ Smalls, 15 September 2010

Ayako Shirasaki is the most amazing up-and-coming pianist around New York City these days. On September 15th, I caught her at Smalls, a club in West Village that distinctly lives up to its name. The place had been set up with rows of folding chairs in front of the grand piano. I preferred to settle down on a high stool at the bar on the side. The tiny place was packed with customers. This was Ayako’s solo piano performance to launch her latest CD, Falling Leaves. She was born in Japan and graduated from the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music with a major in classical music, but she then moved to the States to study jazz at the Manhattan School of Music. She never moved back to her native country, although she keeps close links there. In the name of full disclosure, Ayako and I have become friendly over the past several years I’ve gone to listen to her relatively frequent performances around town.

She started the concert with a Billy Strayhorn classic, followed by Charlie Parker’s Confirmation, thus establishing her jazz credentials right at the outset. On the latter piece, the walking bass she played with her left hand while the right hand chased rapid be-bop phrases was impressive, to say the least. The third tune was also a classic, Round Midnight. This Thelonius Monk masterpiece is so gorgeous that just playing the haunting melody is guaranteed to send shivers down one’s spine. At the same time it is so harmonically complex that it offers endless pitfalls for the performer to stumble on and creating an improvisation that flows logically is a major challenge to most players. Not to Ayako, who breezed through the harmonies with extraordinary versatility. Smalls is the perfect venue for this kind of music: it’s cosy and intimate, not overtly commercial. In many ways it is the prototype image of a New York jazz club from a bygone era.

Ayako Shirasaki is no shrinking violet. Or perhaps it is better to say that her music, like that of Monk, conveys strong emotions without ever becoming schmaltzy. Her technique is amazing and she does virtually anything she wants on the piano. She never fails to amaze me with her left hand virtuosity, no doubt a legacy of her classical training.

The rest of the two-set performance consisted of a number of standards and a few originals, like Monkey Punch, a fluid tune in a brisk tempo; or her own bop creation Three Steps Forward. She played a Bud Powell number in a somewhat aggressive style effortlessly sliding from the Latin groove to a stride piano. Some of the highlights of the evening for me were standards like Someday My Prince Will Come and Turn Out the Lights, to which Ayako gave her on distinct flair. The excellent concert ended with one of my all time favourite tunes, It’s Alright with Me. The title also pretty much summarized my feeling.

Puppets Jazz Bar, featuring Arturo O’Farrill and Ayako Shirasaki, 27 August 2010

Not much earlier, I had joined my friends Nanthi and Vasuki at a fund raiser in support of another excellent small club, Puppets Jazz Bar in the Park Slope neighbourhood of Brooklyn. The club philosophy is that it should offer quality music to aficionados while keeping the entrance free. The club makes its money from drinks and the excellent vegetarian fare that it sells. Unfortunately, this doesn’t appear to be quite enough to pay for the rent. So on this Friday night, the owner, Jaime Aff, had put together an extraordinary group of musicians who played in a nonstop succession from early evening until late at night. Even then there was no cover charge but buckets were sent around to make a voluntary collection from the full house of fans who had gathered in the small space.

The musicians included such local players as the trumpeter John McNeill and guitarist Randy Johnston. As always, Jaime spent much of the time on stage behind his drum kit backing up several of the other performers. The evening also highlighted two excellent yet very different pianists. Ayako Shirasaki was there, this time with a trio. This is another setting that truly suits her style. The other one was Arturo O'Farrill, the son of the legendary Cuban-born orchestra leader Chico O’Farrill (1921-2001). It was rewarding to be able to enjoy—and compare—the two pianists playing back-to-back. Arturo is a big man hulking over the grand piano. Sitting close by but right behind him it was hard to see what was happening on the keyboard as it was hidden behind his broad back. But hearing the music, there was no doubt that what did happen was very interesting. O’Farrill is a very physical player. He beats the keys with powerful chords and Latin tinged patterns. The force is by no means a substitute for sophistication or intended to hide a lack of technique. On the contrary, his chops are definitely inventive and his melodic sense is most pleasurable. It is just that he has this take-no-prisoners approach to his music.

Taka Kigawa @ Le Poisson Rouge, 26 August 2010

Taka Kigawa is a classical pianist who specializes in modern and contemporary music. I can by no means claim to be an expert in the field, but I’ve learned much about the music through Taka who is a friend. He performs regularly around town, but one of his favourite locations is Le Poisson Rouge on Bleecker Street in the Village. It is an unusual venue for classical music, as the spacious place also serves as a restaurant and patrons can order food and drinks to lubricate their artistic experience. Departing from established classical music tradition, Taka also behaves as if he were playing at a club. He dresses casually and communicates with the audience in between the pieces, making personal comments on the music and what it means to him. Consequently, despite the less than easily accessible repertoire, Taka has developed a dedicated following and even on this evening the place was packed. Thanks to Taka’s wife, Michiyo, and our friend Steve who arrived early, we were able to secure seats at a cramped up table right by the stage.

The recital started with Variations for Piano by Anton Webern, a 1936 composition that is particularly close to Taka’s heart. The rather sparse piece silenced the audience forcing us to concentrate on the notes and the spaces in between. From that point on, the mood only intensified. The second composition was Evryali by the French-Greek composer, Iannis Xenakis, which was in stark contrast to the spaciousness of Webern. Evryali hit hard with thick chords and square rhythms. Two contemporary pieces followed: On a Clear Day by the German contemporary composer Matthias Pintscher and Echoes’ White Veil by Jason Eckardt. I have to admit that to my ear Eckardt’s composition was perhaps the most pleasing of the evening, perhaps because the tune has almost an ECM jazz-like flow to it. The composer was present and Taka introduced him on stage to the audience.

Taka rounded off the recital by Pierre Boulez’s First Sonata. As the pianist stepped to the edge of the stage for deep Japanese style bows, the audience broke into a massive applause demanding more. Taka decided to reward the devoted spectatorship with a lovely Debussy rendition that provided a soothing ending to the interesting evening..

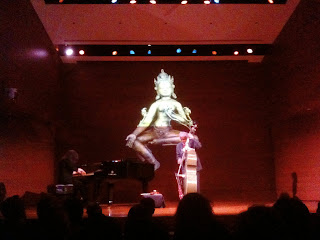

Henry Grimes with Marilyn Crispell @ Harlem in the Himalayas, 24 September 2010

A completely different experience was offered by the bassist Henry Grimes who partnered with the pianist Marilyn Crispell at the Rubin Museum of Art as part of the museum’s Harlem in the Himalayas –series (the Rubin Museum collections focus on Himalayan arts and culture). This concert took rather a free form, with both of the musicians having earned their laurels in the avant garde jazz scene of the 1960s and 1970s.

Henry Grimes’ story is quite incredible and in some ways illustrative of the situation of jazz musicians in the United Sates. The nation hardly treats the masters of its native art form with much reverence. Grimes was one of the top bassists in the heyday of experimental jazz, trusted by such luminaries as Sonny Rollins and McCoy Tyner, as well as by more avant garde experimenters like Albert Ayler, Don Cherry and Archie Shepp. Then in the late-1960s, on a concert tour to the West Coast with Al Jarreau and Jon Hendricks, Grimes’ bass was broken and he could not afford to repair it. The Philadelphia man was thus stranded in Los Angeles, without money and a job. This unfortunate episode led to the leading bass man dropping out of the music scene altogether and working as a manual labourer and maintenance man for over three decades. During this period, writing poetry was his creative outlet. Finally, in 2002 he was discovered working in LA by William Parker, a travelling fan from Georgia who then gave Grimes a bass. The old pro went into intensive practice and made his highly successful return to the New York music scene already the following year! At the tender age of 70, he added a second instrument to his repertoire, debuting on the violin!

The performance that night had a high level of energy, with intensive periods of crescendo and overwhelming cascades of notes interspersed with contemplative rubato passages during which Grimes frequently bowed his bass. At one point he also engaged in a dialogue with the piano on his newly found violin. Marilyn Crispell is also a veteran of the contemporary school of acoustic jazz that spurns the conventions of the more traditional strains of the genre. For a decade she played with the innovative composer/saxophonist Anthony Braxton and has performed with many other top names of free jazz persuasion. Not unexpectedly, then, the duo performance was scarce on the more common jazz idiom. Henry Grimes’ bass playing did contain elements of the blues and was occasionally even swinging, despite the fact that basically none of the pieces were based on a chord structure or a steady beat. The piano was even less ‘jazzy’ with Crispell creating whirlwinds of notes that flowed freely over the entire range of the keyboard, at times using the piano more as a percussive instrument, often playing arpeggios like on a harp.

Chick Corea @ Highline Ballroom, 1 October 2010

Yoko couldn’t believe that I would get tickets for Friday night when I mentioned the forthcoming Chick Corea Trio performance to her just two days before. In Tokyo, she said, Chick Corea would sell out at least half a year in advance. I am sure she is right that this would be the case in Japan; but not in the States. There are two reasons to this. First and most obviously, New York City has so much going on that even a big name will not be able to sell out his concerts easily. Secondly, jazz here where it was born seems now to be too intellectual music for most of the people. It seems fair to say that America today embraces a culture that glorifies wealth, violence and ignorance—ingredients that characterize much of the popular music of today—and there is a strong anti-elitist stream in the country that is reflected in all spheres, including politics (just think of the Tea Party movement!). Not to paint the whole nation with too broad a brush, I hasten to add, there are very many Americans in this big country who appreciate more sophisticated aesthetics and even tonight the huge locale that is the Highline Ballroom in Chelsea was quite packed.

The Chick Corea Trio consisted of Christian McBride on bass, Brian Blade on drums, and the master himself at the piano. He was his jovial self chatting to the audience in a friendly manner before the trio got to work. The concert was set to start at 8 pm and just ten minutes past the hour when no-one appeared on stage someone started a round of applause that the entire hall joined in. This was repeated in about another ten minutes. When the band appeared on stage shortly after, Chick Corea asked, “Are we too early?”

The trio started with a Kurt Weill tune, displaying the amazing lightness of Chick Corea’s touch on the ivory. He just seemed to float on it totally effortlessly. Next came an amazing interpretation of a prelude by A. Scriabin, maybe doing it more justice than the composer had himself ever foreseen when he wrote the beautiful and harmonically complex piece. In Corea’s interpretation, it had a lovely ethnic feel and ended with some well timed hand claps by the leader to accentuate the rhythm. It also was the first piece in which the incredibly talented Christian McBride played a memorable solo.

A Monkish tune followed, which Corea confirmed later as being a tribute to the late genius. McBride again played an impressive solo. The bass player is these days seen as something like Ron Carter was two decades ago, towering over the field. McBride is a guaranteed crowd pleaser – and he is truly amazing – but sometimes he appears a prisoner of his own superior technique that at times seems to obscure the purpose of his solos.

A lovely moment followed with a beautiful bolero in which Corea and McBride cooperated wonderfully in unison passages as Blake worked his array of cymbals in a highly sensitive manner. All in all, throughout the evening the trio played together seamlessly. The music was beautiful and Corea’s piano playing so effortless that it really seemed light as a feather. Yet, perhaps because of the size of the locale and the location of our table on the balcony overlooking the stage, the performance remained a bit un-engaging and distant.

Stanley Clarke Band featuring Hiromi @ Blue Note, 3 October 2010

Let me state it upfront: The Stanley Clarke Band featuring Hiromi produced the best concert I have witnessed in a long time. We caught the group on the last show of a six night engagement at the Blue Note in West Village. Despite the cold rain and the fact that it was 10 pm on a Sunday night, a long line had formed on the sidewalk outside of the club, a testimony to the star status of the leader. When the Philadelphia native (like the elder Grimes) Stanley Clarke burst onto the scene in the 1970s he was an immediate sensation. The lanky teenager handled the upright bass with amazing dexterity and musicality. Like so many others, I was totally taken by his playing with Chick Corea’s original Return to Forever band. Clarke was soon making his own records as a leader while being in demand as a sideman.

At the Blue Note the band featured Ruslan Sirota on electric keyboards and Ronald Bruner, Jr. on drums. But the start of the evening was Hiromi, the piano phenomenon who is making waves on the music scene on both sides of the Pacific. Hiromi Uehara is another Japanese child prodigy who made her debut as orchestra soloist at 12. Now at 31 Hiromi has recorded six excellent jazz CDs under her own name.

The entire band played like a single unit, a result of tight arrangements and discipline imposed by the leader. This didn’t take anything away from the spontaneity or creative of the music. On the contrary, this created an amazing tension in the music that was released during periods of untamed improvisation. While the tall and still boyish Stanley Clarke—this time focusing entirely on his acoustic bass—painted some of the most lyrical pictures of the evening in his solos, Hiromi was entirely uncontrollable. The diminutive pixie-like pianist went wild on the grand piano, jumping on her seat as she spanned the entire range of the 88 keys, playing furious runs or beating dense chords. Always inventive, Hiromi’s playing avoids any clichés just relying on her amazing technique and most of all talent. It was clear that it was not only the audience who were fascinated with her playing, but she equally inspired the veteran bassist and his band.

These opportunities of hearing half a dozen highly skilled yet so different pianists again proved that the only limits there are to the musical expression are between the ears of the artist.