“It’s Galungan and I’m very busy,” Putri said as she was pouring me a drink. She works at the hotel where I was staying. It was already close to midnight and she would have a short night. Although she said she lived close by here in Nusa Dua, during the festival she would have to go to her parental village, which involves a 1.5 hour ride on her moped. And she will have to be ready to go to the temple to make offerings to ancestors with her family at 5:30 am. Galungan is a Hindu festival, closely related to Diwali, the festival of light celebrated in India. But Galungan – like Hinduism here in general – has a distinct Balinese twist. First, unlike the annual Diwali, Gadung is celebrated twice a year and celebrates the creation of the world. For Putri and many others like her employed in the booming commercial sector the traditional festival is a source of both devotion and stress. Tradition is alive and well on Bali.

ting.”

Bali has the reputation of being as close to paradise as any place on earth. The mostly Hindu island in the world’s largest Muslim nation is known for its temples, relaxing lifestyle, friendly people and beaches of white sand. But there are mounting pressures that threaten the paradise-like setting. A place whose charm so much depends on its beauty and clean nature is particularly vulnerable to environmental problems.

The most obvious pressure comes from the sheer number of people. The tiny island has some 3.5 million permanent inhabitants, making it one of the most densely populated places on the planet. This is particularly striking to me, as my own country of birth lies at the opposite end of the spectrum: Finland with sixty times the land area of Bali has just 5 million people. Of course, Bali’s tropical climate and fertile soils have in the first place been able to support such a large and growing population, unlike the frigid conditions up north. Still, the place is increasingly crowded and despite the recent rapid urbanization it is overpopulated. As reported in The Jakarta Post (30 April 2010), according to Indonesian national standard, the maximum population to be supported in Bali in a sustainable manner would only be about 1.6 million people or less than half the current population.

The urban centres themselves present a slew of problems. With haphazard growth and inadequate infrastructure, pollution runs into the rivers and pristine places are transformed into townships. Denpasar, the capital, is now like a miniature Jakarta, crowded with people, cars, mopeds and pollution. The city has a distinct waste management problem that is acknowledged by Indonesian researchers and environmentalists. The city alone produces more than 1,500 m3 of garbage every day, rendering the city planners’ beautification efforts futile. Other growing urban centres are quickly following in its destructive path.

Nusa Dua at the southern tip of the island is an ecosystem in itself. Developed for tourism, the area is built with self-sustaining hotel complexes complete with numerous restaurants, spas, pools and sporting facilities. The entire area is spotlessly clean, neat and well organized with straight roads and perfectly manicured lawns. The main shopping centre, Bali Collection, contains a complex of shops and restaurants where the prices are fixed to a level that would be far above affordable to locals used to viewing bargaining as a competitive, if good-humoured and friendly sport.

Despite this cleanliness, tourism is one of the greatest causes of strain to Bali’s environment. Again, it’s the sheer numbers of people visiting the island. There are 1.9 million visitors annually to the tiny island! The Balinese receive the visitors well and are very tolerant of their sometimes less than gracious ways. In fact, the locals are so tolerant that Indonesian Muslim terrorists bombed entertainment establishments in 2002 and 2005. The earlier bombing in Kuta killed 202 people, including 88 Australian tourists. This put a dent into Bali’s reputation as a party destination and somewhat reduced its popularity among Australians and other Westerners. But whatever slack developed, it has been quickly taken over by others. Apart from the Japanese who have been there for a long time, Chinese tourists are increasingly visible, although most of them seem to be young couples or move only in small groups. What struck me in Nusa Dua was the number of Russians. The beach was crowded with shapely blonds trying to turn their colour darker in places where their tiny bikinis didn’t cover the flesh. The men already tended to sport a naturally redder colour on their bellies, which they started to fill with the refreshing Bingtang or Bali Hai beers from an early hour.

Tourism is blamed for overcrowding the island and straining its environment. In an article with the website Bali Discovery (18 May 2009), the Executive Director of WALHI, an environmental watchdog, Agung Wardana in particular highlights the role of tourism in depleting Bali’s precious water resources. He estimates that every hotel room adds around 3,000 litres to the daily consumption of water. And the golf courses that are converting agricultural land to artificial parks for the benefit of rich and spoiled visitors add another 3 million litres a day to the consumption. This can be contrasted with the average of only 200 litres per day used by the local Balinese. There have been well justified calls for limiting the number of tourists and the construction of new facilities to accommodate them.

My purpose for being here was attending an international meeting, so one afternoon my fellow participants and I embarked on a cultural tour heading towards the temples in Taman Ayun and Tanah Lot. We passed through the booming town of Kuta, first driving through the touristic area with its rows of bars, restaurants and shops; then moving to the more traditional quarters where the locals reside. Ayu, our talkative guide, pointed out the canal running in parallel to the street, suggesting that it would not be a good idea to take a dip there. “The town has grown so quickly and there’s no sewage treatment. These canals used to be nice, actually,” she commented.

Nevertheless, the town does not by any means give an impression of a slum. It all looks rather upbeat unlike many others elsewhere in the developing world (or the USA). Nobody has the time to loiter around, as everyone goes about their business. The Galungan decorations are everywhere. Tall decorated wooden poles line the streets and statues by the numerous temples have been dressed up in checkered black and white clothes – yin and yang – intended to ward off the evil.

Ayu whose name translates into ‘beautiful’ keeps up a running commentary on the history and culture of Bali, as well as the present we can observe as we drive on. Ayu is a rather tall and lively girl whose constant white smile does indeed make her live up to her name. Both Ayu and Putri at the hotel would dispel any preconceived notions of tiny, waif-like Indonesian girls, neither one being particularly petite or shy.

We continue further inland and see construction everywhere. “Corn to concrete,” the observant Ayu remarks. Indeed, in the outskirts of Kuta farmland is incessantly being converted into buildings. But still every available plot in between has been dedicated to small rice paddies. Farmers still keep cows that roam freely in open spaces.

This land transformation – from agriculture and forest into cities, roads and, yes, hotels and golf courses – is one of the biggest problems affecting the future sustainability of the environment and even the economy of Bali. Apart from converting beautiful landscapes into sprawl, it negatively affects the ecological and water balance on the island. It even threatens food production. Every year, tracts of agricultural land is converted into non-agricultural uses.

It started to rain and the landscape turned dark. The traffic was really bad and we were barely moving forward. In the nearly two hours in the car we had gotten only half way where we wanted to go. Suddenly the driver had had enough and without saying a word decided to turn the vehicle around blocking the traffic further. We then headed back and found a roundabout route between agricultural fields where fewer drivers had wandered. Here the landscape was still serene with terraced paddies glistening wet. In spite of the rain that was getting heavier, some farmers were still working their fields. The hillsides were forested.

On the way, we made a stop at a private smaller place of worship at a traditional Balinese house in Baha Village. We caught the proprietor preparing candles and offerings to the deities. Dressed in a yellow blouse and a sarong, she went around from one shrine to the next, placing the candle and the offerings, then put her hands together in a silent prayer.

At the big temple at Taman Ayun the mood was dampened by the rain, but the hawkers along the parking lot beckoned us to shop for trinkets and soft drinks. No doubt, their business would have been better in less inclement weather. More and more busses brought in tourists as we entered. The temple complex is very impressive. Built in 1634 as the main temple of the historical Mengwi Kingdom, the area consists of a huge number of multilayered shrines known as Meru. In the middle yard there is a tower with wooden bells or Kulkul. The entire area is surrounded by a moat.

Wet and tired of sitting in the traffic in between the sights, we continued towards our final destination. Even Ayu was rather low key, only promising that the ride would not take long to reach Tanah Lot on the coast. The place turned out to be extraordinarily beautiful, the small temple of Tanah Lot being perched on a rock protruding into the Timor Sea. It has stood there facing the sometimes stormy (like now) sea since the 16th century when it was established by the Javanese priest Danghyan Nirartha. This was a spot from which to enjoy the sun setting in the west over the sea, but on this particular evening clouds obscured most of the daily spectacle. We were just happy to enjoy refreshing coconuts prepared by three sweet young ladies before settling in for a grilled seafood dinner containing fresh fish, lobster, prawns and mussels.

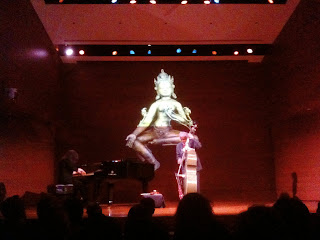

During the evening we were also treated to a delightful performance of traditional Balinese dance. The dancers in delicate outfits glittering with colour and gold performed elaborate dramas from history and mythology. The movements of their eyes are as important as the movement of other parts of the body. A skilful band of stone-faced musicians sitting on the floor behind their Gamelan instruments produced a hypnotic yet dynamic accompaniment to the dance. Later, we witnessed a performance unique to the Tanah Lot region. The music accompanied Barong, a story-telling dance about the fight between good and evil. Completely different from the Gamelan, the music reminded me more of the rituals seen in the South Pacific.

On a different night, I grabbed a taxi to Kuta in order to observe first hand the impacts of backpacking and party tourism on a local city. It was around 11 pm when the driver dropped me off at one end of the beach boulevard. The strip was quieter than I had thought, probably expecting to see a replica of some similar coastal towns in Thailand. This was not the case, at least yet. There were of course numerous bars lining the street, including the ubiquitous Hard Rock Cafe, but the scene was generally quite sedate. As I strolled along the waterfront, I was several times approached by local men offering young women for massage or hashish and marijuana – a particularly stupid proposition in a country where possession of drugs carries the death penalty. Most often, they only offered ‘transportation’, meaning a ride on the back of their light motorcycle. Nusa Dua was too far to make such offers attractive. Another thing that was conspicuous was the extensive construction that was going on even after midnight on this weekend night. New hotels were coming and traditional quarters were being erased to make space for them. Clearly, the local financiers and tourist industry were not paying heed to the warning calls about overcrowding the island or overextending its environment.

Bali is still beautiful and the Timor Sea surrounding it is still full of fish and accommodating to humans who wish to join them for a swim. Ample water is a key element of Bali’s attraction. It is essential equally for the survival of the traditional way of life and agriculture and the tourism-based economy. One can only hope that the quest for money will not entirely spoil the basis of which life and the rich culture rely on. At least today, we can still enjoy the beauty and hospitality of Bali and its people to the soothing sounds of Gamelan.